Leadership within La Eme is not determined by elections or formal titles in the traditional sense; it is earned through respect, proven loyalty, and demonstrated capability in both violence and organization. A member’s reputation—built over years of service in prison or on the streets of Los Santos—is the primary factor in rising to a position of authority. Those who can coordinate operations, settle disputes efficiently, and inspire obedience among soldiers are naturally elevated by their peers and recognized as leaders. When a leader dies, is imprisoned without communication, or loses credibility due to failure or betrayal, the replacement process is often informal but strict. Trusted carnales or senior members convene, either directly or through intermediaries, to determine who is most capable of assuming control over a given area, operation, or prison faction. The new leader must demonstrate both competence and unwavering commitment to La Eme’s codes, often proving themselves through acts of enforcement, successful organization of criminal activity, or even sanctioned violence to reinforce authority.

Consensus and peer approval play a role, but it is largely based on power and respect rather than a formal vote. Rivalries can emerge during transitions, and power struggles are common, sometimes resulting in internal purges or sanctioned hits against potential challengers. However, the overarching goal remains the stability and continuity of La Eme’s operations. The gang’s decentralized but disciplined hierarchy allows multiple leaders to coexist, each controlling their own network while remaining accountable to the broader organization.

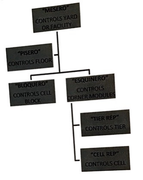

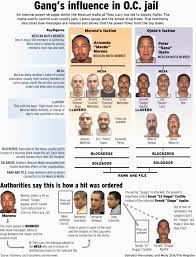

La Eme operates with a hierarchical structure that blends formal roles with influence earned through respect, reputation, and proven loyalty. While the organization is highly secretive, law enforcement and former members have identified several key ranks, both inside the San Andreas prison system and on the streets of Los Santos, where the gang exerts control over its Sureño affiliates. At the top are the Emeros, the made members who have full initiation into La Eme. Emeros hold ultimate authority in both prison and street operations, capable of issuing orders, authorizing hits, and

managing taxation of local gangs. Within this rank, certain members achieve greater influence based on seniority, connections, and their ability to control large networks of associates. Even within the Emeros, power is often fluid, with respect and fear determining who wields the most real-world authority.

managing taxation of local gangs. Within this rank, certain members achieve greater influence based on seniority, connections, and their ability to control large networks of associates. Even within the Emeros, power is often fluid, with respect and fear determining who wields the most real-world authority.Beneath the Emeros are the Soldados, the foot soldiers who carry out day-to-day enforcement, including contract killings, assaults, extortion, and collection of drug taxes. Soldados may also serve as liaisons between La Eme leadership and lower-level street gangs, ensuring compliance and relaying orders. In prison, Soldados are the ones directly supervising other inmates, coordinating activities in cells or yards, and maintaining discipline among those under their authority. Below Soldados are the Affiliates or Helpers, usually younger gang members or low-level Sureños who have pledged allegiance to La Eme but have not yet been fully initiated. These members perform minor tasks, act as runners for drugs and money, and prove themselves through obedience and loyalty. Helpers are often under the direct supervision of Soldados and are expected to demonstrate readiness for eventual promotion to Soldado status. Other important but less formal positions include Camaradas, who are trusted advisors and veterans that provide guidance in both street and prison operations. While they may not hold direct authority over a territory, their counsel is highly respected and can influence leadership decisions. On the streets of Los Santos, the hierarchy mirrors the prison structure but often overlaps with the local Sureño gangs. Leaders in neighborhoods, known as Street Lieutenants, enforce La Eme’s orders, manage local crews, and oversee operations like drug distribution, extortion, and protection rackets. They are accountable to Emeros but have discretion in day-to-day decisions, as long as they maintain revenue flow and loyalty. The gang’s structure emphasizes both obedience and initiative: members are expected to follow orders without question but also to demonstrate the ability to manage operations, resolve conflicts, and maintain control over territory. The combination of formal rank, earned respect, and fear ensures La Eme’s dominance both in prison and across the streets of Los Santos.

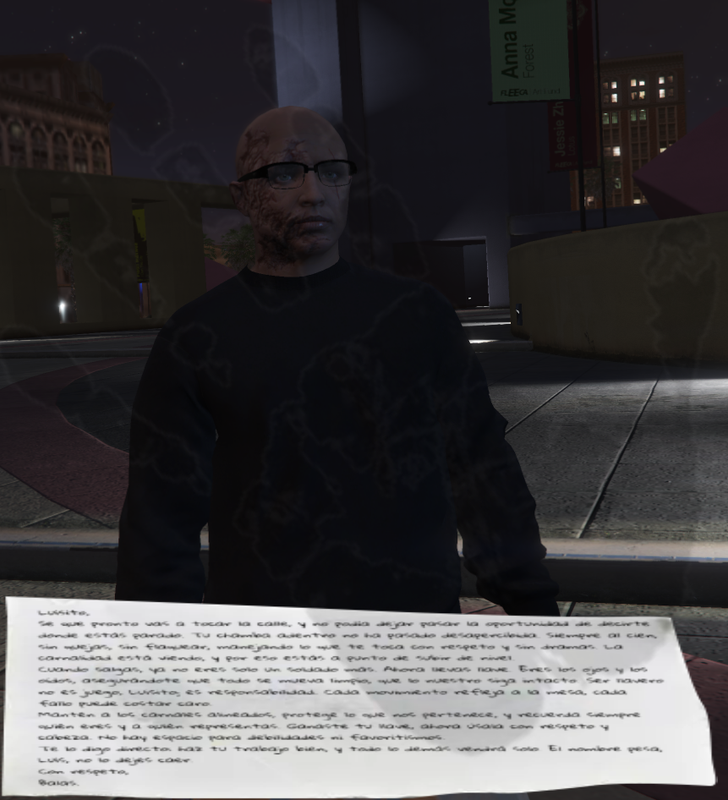

Authority between cliques and neighborhoods in La Eme is maintained through a combination of fear, respect, and structured oversight. The organization functions almost like a central government, with its leadership—mainly Emeros—sitting at the top and local street leaders acting as governors of their respective territories. These leaders ensure that the orders from prison or senior La Eme members are executed without question, including the collection of drug “taxes,” enforcement of discipline, and retaliation against rivals. Each clique or neighborhood gang that aligns with La Eme operates under the Sureño banner but retains some autonomy. This autonomy is carefully balanced with accountability: local leaders are responsible for reporting up the chain of command and demonstrating that their clique contributes to La Eme’s broader influence. Failure to comply—whether through refusal to pay taxes, insubordination, or involvement in unsanctioned violence—can result in swift and often lethal punishment. Communication is key to maintaining this authority. Orders are transmitted through a network of trusted Soldados, Camaradas, and messengers, both in-person and through covert methods such as coded letters, visitors to the prisons, or even sign language. These communication channels allow La Eme to coordinate operations, manage disputes, and assert authority over neighborhoods that are geographically distant from their core strongholds. Territorial control is reinforced through demonstrations of power. If a clique shows resistance or fails to enforce La Eme directives, violent reprisal often follows, sending a clear message to neighboring gangs. Public displays—such as shootings, stabbings, or even graffiti marking a sanctioned “hit”—cement the organization’s dominance and discourage defiance. Respect and reputation also play a role. Veteran members who are feared for their ruthlessness are often dispatched to new or rebellious neighborhoods to remind cliques of the consequences of disobedience. In some cases, leadership transitions are handled diplomatically, with new street lieutenants being mentored by senior members to ensure smooth enforcement of authority. This combination of structured hierarchy, communication networks, and a culture of fear ensures that La Eme maintains effective control over its cliques and neighborhoods, even in a sprawling urban environment like Los Santos. Leadership within La Eme is not determined by elections or formal titles in the traditional sense; it is earned through respect, proven loyalty, and demonstrated capability in both

violence and organization. A member’s reputation—built over years of service in prison or on the streets of Los Santos—is the primary factor in rising to a position of authority. Those who can coordinate operations, settle disputes efficiently, and inspire obedience among soldiers are naturally elevated by their peers and recognized as leaders. When a leader dies, is imprisoned without communication, or loses credibility due to failure or betrayal, the replacement process is often informal but strict. Trusted carnales or senior members convene, either directly or through intermediaries, to determine who is most capable of assuming control over a given area, operation, or prison faction. The new leader must demonstrate both competence and unwavering commitment to La Eme’s codes, often proving themselves through acts of enforcement, successful organization of criminal activity, or even sanctioned violence to reinforce authority. Consensus and peer approval play a role, but it is largely based on power and respect rather than a formal vote. Rivalries can emerge during transitions, and power struggles are common, sometimes resulting in internal purges or sanctioned hits against potential challengers. However, the overarching goal remains the stability and continuity of La Eme’s operations. The gang’s decentralized but disciplined hierarchy allows multiple leaders to coexist, each controlling their own network while remaining accountable to the broader organization. La Eme operates with a hierarchical structure that blends formal roles with influence earned through respect, reputation, and proven loyalty. While the organization is highly secretive, law enforcement and former members have identified several key ranks, both inside the San Andreas prison system and on the streets of Los Santos, where the gang exerts control over its Sureño affiliates.

violence and organization. A member’s reputation—built over years of service in prison or on the streets of Los Santos—is the primary factor in rising to a position of authority. Those who can coordinate operations, settle disputes efficiently, and inspire obedience among soldiers are naturally elevated by their peers and recognized as leaders. When a leader dies, is imprisoned without communication, or loses credibility due to failure or betrayal, the replacement process is often informal but strict. Trusted carnales or senior members convene, either directly or through intermediaries, to determine who is most capable of assuming control over a given area, operation, or prison faction. The new leader must demonstrate both competence and unwavering commitment to La Eme’s codes, often proving themselves through acts of enforcement, successful organization of criminal activity, or even sanctioned violence to reinforce authority. Consensus and peer approval play a role, but it is largely based on power and respect rather than a formal vote. Rivalries can emerge during transitions, and power struggles are common, sometimes resulting in internal purges or sanctioned hits against potential challengers. However, the overarching goal remains the stability and continuity of La Eme’s operations. The gang’s decentralized but disciplined hierarchy allows multiple leaders to coexist, each controlling their own network while remaining accountable to the broader organization. La Eme operates with a hierarchical structure that blends formal roles with influence earned through respect, reputation, and proven loyalty. While the organization is highly secretive, law enforcement and former members have identified several key ranks, both inside the San Andreas prison system and on the streets of Los Santos, where the gang exerts control over its Sureño affiliates.At the top are the Emeros, the made members who have full initiation into La Eme. Emeros hold ult

imate authority in both prison and street operations, capable of issuing orders, authorizing hits, and managing taxation of local gangs. Within this rank, certain members achieve greater influence based on seniority, connections, and their ability to control large networks of associates. Even within the Emeros, power is often fluid, with respect and fear determining who wields the most real-world authority. Beneath the Emeros are the Soldados, the foot soldiers who carry out day-to-day enforcement, including contract killings, assaults, extortion, and collection of drug taxes. Soldados may also serve as liaisons between La Eme leadership and lower-level street gangs, ensuring compliance and relaying orders. In prison, Soldados are the ones directly supervising other inmates, coordinating activities in cells or yards, and maintaining discipline among those under their authority. Below Soldados are the Affiliates or Helpers, usually younger gang members or low-level Sureños who have pledged allegiance to La Eme but have not yet been fully initiated. These members perform minor tasks, act as runners for drugs and money, and prove themselves through obedience and loyalty. Helpers are often under the direct supervision of Soldados and are expected to demonstrate readiness for eventual promotion to Soldado status. Other important but less formal positions include Camaradas, who are trusted advisors and veterans that provide guidance in both street and prison operations. While they may not hold direct authority over a territory, their counsel is highly respected and can influence leadership decisions. On the streets of Los Santos, the hierarchy mirrors the prison structure but often overlaps with the local Sureño gangs. Leaders in neighborhoods, known as Street Lieutenants, enforce La Eme’s orders, manage local crews, and oversee operations like drug distribution, extortion, and protection rackets. They are accountable to Emeros but have discretion in day-to-day decisions, as long as they maintain revenue flow and loyalty. The gang’s structure emphasizes both obedience and initiative: members are expected to follow orders without question but also to demonstrate the ability to manage operations, resolve conflicts, and maintain control over territory. The combination of formal rank, earned respect, and fear ensures La Eme’s dominance both in prison and across the streets of Los Santos.

imate authority in both prison and street operations, capable of issuing orders, authorizing hits, and managing taxation of local gangs. Within this rank, certain members achieve greater influence based on seniority, connections, and their ability to control large networks of associates. Even within the Emeros, power is often fluid, with respect and fear determining who wields the most real-world authority. Beneath the Emeros are the Soldados, the foot soldiers who carry out day-to-day enforcement, including contract killings, assaults, extortion, and collection of drug taxes. Soldados may also serve as liaisons between La Eme leadership and lower-level street gangs, ensuring compliance and relaying orders. In prison, Soldados are the ones directly supervising other inmates, coordinating activities in cells or yards, and maintaining discipline among those under their authority. Below Soldados are the Affiliates or Helpers, usually younger gang members or low-level Sureños who have pledged allegiance to La Eme but have not yet been fully initiated. These members perform minor tasks, act as runners for drugs and money, and prove themselves through obedience and loyalty. Helpers are often under the direct supervision of Soldados and are expected to demonstrate readiness for eventual promotion to Soldado status. Other important but less formal positions include Camaradas, who are trusted advisors and veterans that provide guidance in both street and prison operations. While they may not hold direct authority over a territory, their counsel is highly respected and can influence leadership decisions. On the streets of Los Santos, the hierarchy mirrors the prison structure but often overlaps with the local Sureño gangs. Leaders in neighborhoods, known as Street Lieutenants, enforce La Eme’s orders, manage local crews, and oversee operations like drug distribution, extortion, and protection rackets. They are accountable to Emeros but have discretion in day-to-day decisions, as long as they maintain revenue flow and loyalty. The gang’s structure emphasizes both obedience and initiative: members are expected to follow orders without question but also to demonstrate the ability to manage operations, resolve conflicts, and maintain control over territory. The combination of formal rank, earned respect, and fear ensures La Eme’s dominance both in prison and across the streets of Los Santos.Authority between cliques and neighborhoods in La Eme is maintained through a combination of fear, respect, and structured oversight. The organization functions almost like a central government, with its leadership—mainly Emeros—sitting at the top and local street leaders acting as governors of their respective territories. These leaders ensure that the orders from prison or senior La Eme members are executed without question, including the collection of drug “taxes,” enforcement of discipline, and retaliation against rivals. Each clique or neighborhood gang that aligns

with La Eme operates under the Sureño banner but retains some autonomy. This autonomy is carefully balanced with accountability: local leaders are responsible for reporting up the chain of command and demonstrating that their clique contributes to La Eme’s broader influence. Failure to comply—whether through refusal to pay taxes, insubordination, or involvement in unsanctioned violence—can result in swift and often lethal punishment. Communication is key to maintaining this authority. Orders are transmitted through a network of trusted Soldados, Camaradas, and messengers, both in-person and through covert methods such as coded letters, visitors to the prisons, or even sign language. These communication channels allow La Eme to coordinate operations, manage disputes, and assert authority over neighborhoods that are geographically distant from their core strongholds. Territorial control is reinforced through demonstrations of power. If a clique shows resistance or fails to enforce La Eme directives, violent reprisal often follows, sending a clear message to neighboring gangs. Public displays—such as shootings, stabbings, or even graffiti marking a sanctioned “hit”—cement the organization’s dominance and discourage defiance. Respect and reputation also play a role. Veteran members who are feared for their ruthlessness are often dispatched to new or rebellious neighborhoods to remind cliques of the consequences of disobedience. In some cases, leadership transitions are handled diplomatically, with new street lieutenants being mentored by senior members to ensure smooth enforcement of authority. This combination of structured hierarchy, communication networks, and a culture of fear ensures that La Eme maintains effective control over its cliques and neighborhoods, even in a sprawling urban environment like Los Santos.

with La Eme operates under the Sureño banner but retains some autonomy. This autonomy is carefully balanced with accountability: local leaders are responsible for reporting up the chain of command and demonstrating that their clique contributes to La Eme’s broader influence. Failure to comply—whether through refusal to pay taxes, insubordination, or involvement in unsanctioned violence—can result in swift and often lethal punishment. Communication is key to maintaining this authority. Orders are transmitted through a network of trusted Soldados, Camaradas, and messengers, both in-person and through covert methods such as coded letters, visitors to the prisons, or even sign language. These communication channels allow La Eme to coordinate operations, manage disputes, and assert authority over neighborhoods that are geographically distant from their core strongholds. Territorial control is reinforced through demonstrations of power. If a clique shows resistance or fails to enforce La Eme directives, violent reprisal often follows, sending a clear message to neighboring gangs. Public displays—such as shootings, stabbings, or even graffiti marking a sanctioned “hit”—cement the organization’s dominance and discourage defiance. Respect and reputation also play a role. Veteran members who are feared for their ruthlessness are often dispatched to new or rebellious neighborhoods to remind cliques of the consequences of disobedience. In some cases, leadership transitions are handled diplomatically, with new street lieutenants being mentored by senior members to ensure smooth enforcement of authority. This combination of structured hierarchy, communication networks, and a culture of fear ensures that La Eme maintains effective control over its cliques and neighborhoods, even in a sprawling urban environment like Los Santos.

La Eme formed in the late 1950s inside the youth detention system of Los Santos, specifically at the Deuel Vocational Institution, which held young Hispanic offenders from across the city. At the time, gangs in Los Santos’ barrios were highly fragmented, with neighborhood loyalty often outweighing any broader sense of unity. Violence was rampant both on the streets and inside juvenile facilities, leaving many young Mexican-American inmates vulnerable to predation from other groups. It was in this environment that Luis “Huero Buff” Flores, along with a small cadre of fellow incarcerated gang members, envisioned an organization that could unite the city’s disparate Hispanic inmates under a single banner. Their goal was simple but ruthless: protect themselves and their people from external threats while establishing a network of influence that could reach beyond the prison walls. From the beginning, La Eme was structured around the concept of absolute loyalty and fear. Founding members recruited individuals who were known for their violent tendencies, tactical intelligence, or street credibility. By forging bonds between former rivals, the gang created a unified force that could dominate the juvenile detention system, and eventually adult prisons, through intimidation, extortion, and sheer brutality. The name “La Eme,” literally “the M,” served as both a symbol of Mexican-American pride and a clear declaration of dominance. Early members also adopted rituals

, symbols, and a code of conduct that emphasized obedience, secrecy, and violence as necessary tools to protect the organization and assert control.

, symbols, and a code of conduct that emphasized obedience, secrecy, and violence as necessary tools to protect the organization and assert control.What set La Eme apart from other gangs of the era was its vision of organization. Unlike typical street gangs that operated strictly along neighborhood lines, La Eme sought to create a “gang of gangs,” a network that could integrate members from multiple barrios in Los Santos under a shared hierarchy and ideology. This allowed them to enforce rules and exert influence not only in the prison system but also across the city’s streets, giving rise to a reach that would eventually extend to nearly every Hispanic gang in Southern Los Santos. By the time members were released back onto the streets, they brought with them the authority, networks, and fear cultivated behind bars, establishing La Eme as both a prison and street-based criminal empire. La Eme’s origins trace back to several neighborhoods in Los Santos where the city’s earliest Hispanic street gangs were already established. While the gang itself formally coalesced inside the Deuel Vocational Institution, its members came from barrios scattered across East, South, and Central Los Santos. Areas like Boyle Heights, East Vinewood, El Corona, and Harbor City were some of the primary recruiting grounds for the organization, as these neighborhoods had deep histories of gang activity dating back to the 1940s and 1950s. The founders were able to leverage existing rivalries and alliances, convincing local street gang leaders to send their toughest, most loyal young men into the prison system to join La Eme. Boyle Heights, in particular, served as a critical hub. Known for its dense population of Mexican-American families and a network of small but competitive gangs, it provided a pool of recruits who were already steeped in street culture and familiar with the codes of loyalty and violence that La Eme would enforce. Similarly, neighborhoods like East Vinewood and El Corona contributed members who brought with them unique skills, from drug distribution experience to strategic knowledge of local law enforcement patterns. The early La Eme members often maintained ties with their home barrios, allowing the gang to extend its influence beyond prison walls almost immediately. What distinguished La Eme from other groups in these neighborhoods was its ability to unify members from otherwise rival gangs under a common purpose. By the time its members were released back onto the streets, La Eme already had a foothold in several of Los Santos’ most notorious barrios. Its members acted as emissaries of the gang’s authority, collecting taxes, enforcing orders, and consolidating power in ways that local street gangs alone could never achieve. This early geographic spread laid the foundation for La Eme’s dominance over the Hispanic gang landscape in Los Santos, making it the central authority that would eventually control or influence nearly every Sureño-affiliated crew in the city.

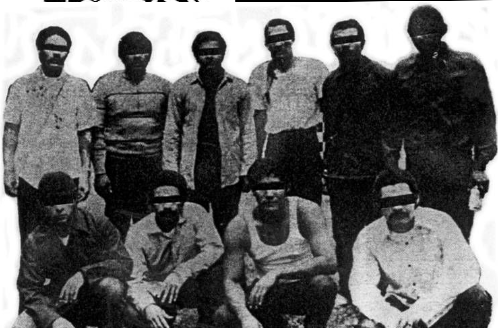

The founding members of La Eme were a small group of thirteen young men, primarily Mexican-American, who were incarcerated at the Deuel Vocational Institution in Los Santos during the late 1950s. Among them, Luis “Huero Buff” Flores is widely recognized as the central figure and visionary behind the organization. Flores, a member of the Barrio Hawaiian Gardens gang, had already established a reputation for toughness and cunning on the streets of Los Santos, and he saw an opportunity to protect Hispanic inmates from other racial groups while creating a unified power structure that could extend beyond prison walls. Another key founder was Rudy “Cheyenne” Cadena, who became known for his ruthless enforcement tactics and strategic mind. Cadena was instrumental in establishing the gang’s early codes of conduct, including the blood-in, blood-out policy that would define La Eme membership for decades. He ensured that loyalty, obedience, and fear were central pillars of the gang’s structure, solidifying the authority of its members both inside the facility and later on the streets. Other early members came from diverse Los Santos neighborhoods, each bringing their own street experience and gang affiliations. Many had been involved with Eastside or Harbor gangs such as White Fence, Clanton 14, Varrio Nuevo Estrada, and Primera Flats. These men were already accustomed to the culture of territorial disputes, drug

dealing, and violent enforcement, which made them ideal candidates to create a prison-based organization that could command respect and fear. While their individual names are less well-known, collectively they established the foundation of what would become the most influential Hispanic gang in Los Santos. The early La Eme members shared a vision: to consolidate Hispanic power inside prisons, protect themselves from rival groups, and eventually exert influence over street gangs in their home neighborhoods. They formalized their structure with strict rules, ceremonial oaths, and a clear hierarchy of authority. This combination of fear, loyalty, and organization allowed La Eme to transform from a small prison clique into a sprawling criminal enterprise that would come to dominate Los Santos’ Hispanic gang landscape for decades.

dealing, and violent enforcement, which made them ideal candidates to create a prison-based organization that could command respect and fear. While their individual names are less well-known, collectively they established the foundation of what would become the most influential Hispanic gang in Los Santos. The early La Eme members shared a vision: to consolidate Hispanic power inside prisons, protect themselves from rival groups, and eventually exert influence over street gangs in their home neighborhoods. They formalized their structure with strict rules, ceremonial oaths, and a clear hierarchy of authority. This combination of fear, loyalty, and organization allowed La Eme to transform from a small prison clique into a sprawling criminal enterprise that would come to dominate Los Santos’ Hispanic gang landscape for decades.La Eme’s first major conflicts emerged almost immediately after its formation, as the new gang sought to assert dominance over both the prison environment and the Hispanic inmates it intended to control. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, the Deuel Vocational Institution, where La Eme was founded, was a volatile environment rife with racial tension and inter-gang violence. Hispanic inmates were often targeted by more established groups, and the newly formed Mexican Mafia had to establish a reputation of strength quickly in order to survive. One of the earliest and most significant challenges came from within the Hispanic inmate population itself. Many prisoners who were not part of La Eme viewed the gang as an overreaching authority, especially as the organization began enforcing taxes on prison black-market activities and demanding loyalty from street gang affiliates who entered the system. This internal resistance soon escalated into violent confrontations, including stabbings and targeted killings, which served both as punishment and as a warning to others considering defiance. Shortly after La Eme began transferring members to adult prisons, such as San Quentin, conflicts intensified. Rival groups like the newly formed

s of loyalty, often involving violent initiation rituals, and violations of the rules were met with extreme consequences, including death. Maintaining internal discipline in such a violent and high-pressure environment was critical to La Eme’s survival and allowed the gang to solidify its reputation as one of the most feared forces in the prison system. Today, La Eme operates without a single, centralized leader in the traditional sense. Power is distributed among a network of high-ranking members, often referred to as carnales, who maintain control over both prison operations and street-level enforcement throughout Los Santos. These leaders are usually veteran members who have earned respect through years of service, violent acts, and strict adherence to the gang’s codes. Authority is not merely inherited or assumed; it must be earned, and those at the top are responsible for issuing orders, settling disputes, collecting tribute, and overseeing major criminal operations. Even though there isn’t one “kingpin” in charge, some members emerge as more influential than others based on their ability to coordinate large-scale operations and command loyalty from subordinate members. Historically, figures like Rene “Bosko” Blajos held significant sway, consolidating territory and revenue streams from drug distribution, extortion, and street taxation. However, crackdowns and law enforcement operations, such as the massive sweep “Open Casket,” have disrupted visible leadership, creating power vacuums. Despite these disruptions, the hierarchy remains functional. Authority flows from the carnales to trusted lieutenants, who then manage soldados or foot soldiers in both prison and Los Santos neighborhoods. Even incarcerated leaders can exert influence through coded communications, letters, and intermediaries, ensuring that orders reach the streets without direct contact. This decentralized but disciplined structure makes La Eme highly resilient; if one leader is removed, others quickly step in to maintain control.The gang’s leadership today is less about an individual figurehead and more about maintaining a collective reputation of fear, loyalty, and discipline. Decisions—especially violent ones—may require consensus among top-ranking members, but execution often falls to the nearest available operative, whether in prison or on the streets. The result is a sprawling but organized network where power is fluid, yet La Eme’s influence across Los Santos remains unshakable.

s of loyalty, often involving violent initiation rituals, and violations of the rules were met with extreme consequences, including death. Maintaining internal discipline in such a violent and high-pressure environment was critical to La Eme’s survival and allowed the gang to solidify its reputation as one of the most feared forces in the prison system. Today, La Eme operates without a single, centralized leader in the traditional sense. Power is distributed among a network of high-ranking members, often referred to as carnales, who maintain control over both prison operations and street-level enforcement throughout Los Santos. These leaders are usually veteran members who have earned respect through years of service, violent acts, and strict adherence to the gang’s codes. Authority is not merely inherited or assumed; it must be earned, and those at the top are responsible for issuing orders, settling disputes, collecting tribute, and overseeing major criminal operations. Even though there isn’t one “kingpin” in charge, some members emerge as more influential than others based on their ability to coordinate large-scale operations and command loyalty from subordinate members. Historically, figures like Rene “Bosko” Blajos held significant sway, consolidating territory and revenue streams from drug distribution, extortion, and street taxation. However, crackdowns and law enforcement operations, such as the massive sweep “Open Casket,” have disrupted visible leadership, creating power vacuums. Despite these disruptions, the hierarchy remains functional. Authority flows from the carnales to trusted lieutenants, who then manage soldados or foot soldiers in both prison and Los Santos neighborhoods. Even incarcerated leaders can exert influence through coded communications, letters, and intermediaries, ensuring that orders reach the streets without direct contact. This decentralized but disciplined structure makes La Eme highly resilient; if one leader is removed, others quickly step in to maintain control.The gang’s leadership today is less about an individual figurehead and more about maintaining a collective reputation of fear, loyalty, and discipline. Decisions—especially violent ones—may require consensus among top-ranking members, but execution often falls to the nearest available operative, whether in prison or on the streets. The result is a sprawling but organized network where power is fluid, yet La Eme’s influence across Los Santos remains unshakable.Leadership within La Eme is not determined by elections or formal titles in the traditional sense; it is earned through respect, proven loyalty, and demonstrated capability in both violence and organization. A member’s reputation—built over years of service in prison or on the streets of Los Santos—is the primary factor in rising to a position of authority. Those who can coordinate operations, settle disputes efficiently, and inspire obedience among soldiers are naturally elevated by their peers and recognized as leaders. When a leader dies, is imprisoned without communication, or loses credibility due to failure or betrayal, the replacement process is often informal but strict. Trusted carnales or senior members convene, either directly or through intermediaries, to determine who is most capable of assuming control over a given area, operation, or prison faction. The new leader must demonstrate both competence and unwavering commitment to La Eme’s codes, often proving themselves through acts of enforcement, successful organization of criminal activity, or even sanctioned violence to reinforce authority. Consensus and peer approval play a role, but it is largely based on power and respect rather than a formal vote. Rivalries can emerge during transitions, and power struggles are common, som

etimes resulting in internal purges or sanctioned hits against potential challengers. However, the overarching goal remains the stability and continuity of La Eme’s operations. The gang’s decentralized but disciplined hierarchy allows multiple leaders to coexist, each controlling their own network while remaining accountable to the broader organization. La Eme operates with a hierarchical structure that blends formal roles with influence earned through respect, reputation, and proven loyalty. While the organization is highly secretive, law enforcement and former members have identified several key ranks, both inside the San Andreas prison system and on the streets of Los Santos, where the gang exerts control over its Sureño affiliates. At the top are the Emeros, the made members who have full initiation into La Eme. Emeros hold ultimate authority in both prison and street operations, capable of issuing orders, authorizing hits, and managing taxation of local gangs. Within this rank, certain members achieve greater influence based on seniority, connections, and their ability to control large networks of associates. Even within the Emeros, power is often fluid, with respect and fear determining who wields the most real-world authority. Beneath the Emeros are the Soldados, the foot soldiers who carry out day-to-day enforcement, including contract killings, assaults, extortion, and collection of drug taxes. Soldados may also serve as liaisons between La Eme leadership and lower-level street gangs, ensuring compliance and relaying orders. In prison, Soldados are the ones directly supervising other inmates, coordinating activities in cells or yards, and maintaining discipline among those under their authority. Below Soldados are the Affiliates or Helpers, usually younger gang members or low-level Sureños who have pledged allegiance to La Eme but have not yet been fully initiated. These members perform minor tasks, act as runners for drugs and money, and prove themselves through obedience and loyalty. Helpers are often under the direct supervision of Soldados and are expected to demonstrate readiness for eventual promotion to Soldado status. Other important but less formal positions include Camaradas, who are trusted advisors and veterans that provide guidance in both street and prison operations. While they may not hold direct authority over a territory, their counsel is highly respected and can influence leadership decisions. On the streets of Los Santos, the hierarchy mirrors the prison structure but often overlaps with the local Sureño gangs. Leaders in neighborhoods, known as Street Lieutenants, enforce La Eme’s orders, manage local crews, and oversee operations like drug distribution, extortion, and protection rackets. They are accountable to Emeros but have discretion in day-to-day decisions, as long as they maintain revenue flow and loyalty. The gang’s structure emphasizes both obedience and initiative: members are expected to follow orders without question but also to demonstrate the ability to manage operations, resolve conflicts, and maintain control over territory. The combination of formal rank, earned respect, and fear ensures La Eme’s dominance both in prison and across the streets of Los Santos. Authority between cliques and neighborhoods in La Eme is maintained through a combination of fear, respect, and structured oversight. The organization functions almost like a central government, with its leadership—mainly Emeros—sitting at the top and local street leaders acting as governors of their respective territories. These leaders ensure that the orders from prison or senior La Eme members are executed without question, including the collection of drug “taxes,” enforcement of discipline, and

etimes resulting in internal purges or sanctioned hits against potential challengers. However, the overarching goal remains the stability and continuity of La Eme’s operations. The gang’s decentralized but disciplined hierarchy allows multiple leaders to coexist, each controlling their own network while remaining accountable to the broader organization. La Eme operates with a hierarchical structure that blends formal roles with influence earned through respect, reputation, and proven loyalty. While the organization is highly secretive, law enforcement and former members have identified several key ranks, both inside the San Andreas prison system and on the streets of Los Santos, where the gang exerts control over its Sureño affiliates. At the top are the Emeros, the made members who have full initiation into La Eme. Emeros hold ultimate authority in both prison and street operations, capable of issuing orders, authorizing hits, and managing taxation of local gangs. Within this rank, certain members achieve greater influence based on seniority, connections, and their ability to control large networks of associates. Even within the Emeros, power is often fluid, with respect and fear determining who wields the most real-world authority. Beneath the Emeros are the Soldados, the foot soldiers who carry out day-to-day enforcement, including contract killings, assaults, extortion, and collection of drug taxes. Soldados may also serve as liaisons between La Eme leadership and lower-level street gangs, ensuring compliance and relaying orders. In prison, Soldados are the ones directly supervising other inmates, coordinating activities in cells or yards, and maintaining discipline among those under their authority. Below Soldados are the Affiliates or Helpers, usually younger gang members or low-level Sureños who have pledged allegiance to La Eme but have not yet been fully initiated. These members perform minor tasks, act as runners for drugs and money, and prove themselves through obedience and loyalty. Helpers are often under the direct supervision of Soldados and are expected to demonstrate readiness for eventual promotion to Soldado status. Other important but less formal positions include Camaradas, who are trusted advisors and veterans that provide guidance in both street and prison operations. While they may not hold direct authority over a territory, their counsel is highly respected and can influence leadership decisions. On the streets of Los Santos, the hierarchy mirrors the prison structure but often overlaps with the local Sureño gangs. Leaders in neighborhoods, known as Street Lieutenants, enforce La Eme’s orders, manage local crews, and oversee operations like drug distribution, extortion, and protection rackets. They are accountable to Emeros but have discretion in day-to-day decisions, as long as they maintain revenue flow and loyalty. The gang’s structure emphasizes both obedience and initiative: members are expected to follow orders without question but also to demonstrate the ability to manage operations, resolve conflicts, and maintain control over territory. The combination of formal rank, earned respect, and fear ensures La Eme’s dominance both in prison and across the streets of Los Santos. Authority between cliques and neighborhoods in La Eme is maintained through a combination of fear, respect, and structured oversight. The organization functions almost like a central government, with its leadership—mainly Emeros—sitting at the top and local street leaders acting as governors of their respective territories. These leaders ensure that the orders from prison or senior La Eme members are executed without question, including the collection of drug “taxes,” enforcement of discipline, and

retaliation against rivals. Each clique or neighborhood gang that aligns with La Eme operates under the Sureño banner but retains some autonomy. This autonomy is carefully balanced with accountability: local leaders are responsible for reporting up the chain of command and demonstrating that their clique contributes to La Eme’s broader influence. Failure to comply—whether through refusal to pay taxes, insubordination, or involvement in unsanctioned violence—can result in swift and often lethal punishment. Communication is key to maintaining this authority. Orders are transmitted through a network of trusted Soldados, Camaradas, and messengers, both in-person and through covert methods such as coded letters, visitors to the prisons, or even sign language. These communication channels allow La Eme to coordinate operations, manage disputes, and assert authority over neighborhoods that are geographically distant from their core strongholds.Territorial control is reinforced through demonstrations of power. If a clique shows resistance or fails to enforce La Eme directives, violent reprisal often follows, sending a clear message to neighboring gangs. Public displays—such as shootings, stabbings, or even graffiti marking a sanctioned “hit”—cement the organization’s dominance and discourage defiance.Respect and reputation also play a role. Veteran members who are feared for their ruthlessness are often dispatched to new or rebellious neighborhoods to remind cliques of the consequences of disobedience. In some cases, leadership transitions are handled diplomatically, with new street lieutenants being mentored by senior members to ensure smooth enforcement of authority. This combination of structured hierarchy, communication networks, and a culture of fear ensures that La Eme maintains effective control over its cliques and neighborhoods, even in a sprawling urban environment like Los Santos.

retaliation against rivals. Each clique or neighborhood gang that aligns with La Eme operates under the Sureño banner but retains some autonomy. This autonomy is carefully balanced with accountability: local leaders are responsible for reporting up the chain of command and demonstrating that their clique contributes to La Eme’s broader influence. Failure to comply—whether through refusal to pay taxes, insubordination, or involvement in unsanctioned violence—can result in swift and often lethal punishment. Communication is key to maintaining this authority. Orders are transmitted through a network of trusted Soldados, Camaradas, and messengers, both in-person and through covert methods such as coded letters, visitors to the prisons, or even sign language. These communication channels allow La Eme to coordinate operations, manage disputes, and assert authority over neighborhoods that are geographically distant from their core strongholds.Territorial control is reinforced through demonstrations of power. If a clique shows resistance or fails to enforce La Eme directives, violent reprisal often follows, sending a clear message to neighboring gangs. Public displays—such as shootings, stabbings, or even graffiti marking a sanctioned “hit”—cement the organization’s dominance and discourage defiance.Respect and reputation also play a role. Veteran members who are feared for their ruthlessness are often dispatched to new or rebellious neighborhoods to remind cliques of the consequences of disobedience. In some cases, leadership transitions are handled diplomatically, with new street lieutenants being mentored by senior members to ensure smooth enforcement of authority. This combination of structured hierarchy, communication networks, and a culture of fear ensures that La Eme maintains effective control over its cliques and neighborhoods, even in a sprawling urban environment like Los Santos.New members of La Eme are recruited through a highly selective and secretive process, designed to ensure loyalty, capability, and a willingness to uphold the gang’s violent and uncompromising culture. Recruitment begins in the streets, where local Sureño cliques identify potential candidates—often young men from affiliated neighborhoods—who have demonstrated courage, resourcefulness, and a proven commitment to their local gang. Reputation matters above all; word-of-mouth endorsements from trusted members can carry more weight than any formal evaluation. Inside the prison system, recruitment takes a more formalized and ritualistic shape. Prospective members are often “sponsored” by an existing Eme member, usually someone with seniority who vouches for the candidate’s character and abilities. The candidate is observed over time, with their behavior scrutinized for signs of loyalty, discipline, and adherence to gang codes. Tasks assigned during this period often involve demonstrating toughness, such as participating in fights, committing theft, or carrying out attacks on rival gang members—all meant to prove commitment to the b

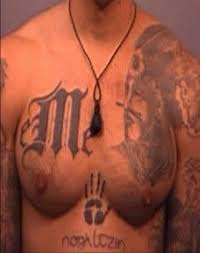

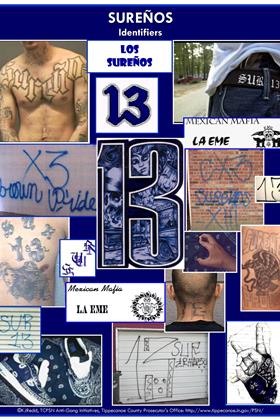

lood-in, blood-out philosophy. The initiation itself is steeped in symbolism and risk. Traditionally, a new member must either draw blood from an enemy or directly participate in a sanctioned act of violence, cementing their loyalty through action rather than words. This act is sometimes performed in the streets under supervision or, more often, inside the prison system where oversight by senior members ensures that the new recruit fully understands the consequences of betrayal. Those who hesitate, fail, or refuse are often punished severely or even killed, reinforcing the stakes of entry. Once a recruit successfully completes initiation, they are formally recognized as a Carnal—a brother of La Eme. Tattoos are often applied to signify their membership, commonly featuring symbols like the black hand, the number 13, or the eagle and snake over crossed knives. Even after formal induction, the new member remains under close supervision, and their loyalty is continually tested through ongoing assignments, enforcement of gang rules, and participation in both street and prison activities. This rigorous recruitment process ensures that La Eme remains highly disciplined, with members who are both fearsome and deeply loyal. It also serves to perpetuate a culture of violence, secrecy, and absolute obedience, allowing the organization to maintain control over its sprawling network of street gangs and prison cliques. Initiation into La Eme is a grueling, high-stakes process that reflects the gang’s blood-in, blood-out philosophy. It is designed not only to prove loyalty but also to instill fear, obedience, and an unwavering commitment to the organization. While specific rituals can vary slightly between neighborhoods and prisons, the core elements remain consistent. For street recruits, initiation often begins with a period of observation and testing by existing members. Potential members are expected to demonstrate courage, resourcefulness, and allegiance to their local clique and the broader La Eme network. Tasks assigned during this period can include theft, enforcement of gang rules, intimidation of rivals, or even participating in assaults. These early tests serve as both a measure of loyalty and a way to integrate the recruit into the gang’s operational hierarchy.

lood-in, blood-out philosophy. The initiation itself is steeped in symbolism and risk. Traditionally, a new member must either draw blood from an enemy or directly participate in a sanctioned act of violence, cementing their loyalty through action rather than words. This act is sometimes performed in the streets under supervision or, more often, inside the prison system where oversight by senior members ensures that the new recruit fully understands the consequences of betrayal. Those who hesitate, fail, or refuse are often punished severely or even killed, reinforcing the stakes of entry. Once a recruit successfully completes initiation, they are formally recognized as a Carnal—a brother of La Eme. Tattoos are often applied to signify their membership, commonly featuring symbols like the black hand, the number 13, or the eagle and snake over crossed knives. Even after formal induction, the new member remains under close supervision, and their loyalty is continually tested through ongoing assignments, enforcement of gang rules, and participation in both street and prison activities. This rigorous recruitment process ensures that La Eme remains highly disciplined, with members who are both fearsome and deeply loyal. It also serves to perpetuate a culture of violence, secrecy, and absolute obedience, allowing the organization to maintain control over its sprawling network of street gangs and prison cliques. Initiation into La Eme is a grueling, high-stakes process that reflects the gang’s blood-in, blood-out philosophy. It is designed not only to prove loyalty but also to instill fear, obedience, and an unwavering commitment to the organization. While specific rituals can vary slightly between neighborhoods and prisons, the core elements remain consistent. For street recruits, initiation often begins with a period of observation and testing by existing members. Potential members are expected to demonstrate courage, resourcefulness, and allegiance to their local clique and the broader La Eme network. Tasks assigned during this period can include theft, enforcement of gang rules, intimidation of rivals, or even participating in assaults. These early tests serve as both a measure of loyalty and a way to integrate the recruit into the gang’s operational hierarchy.Within the prison system, initiation becomes more formal and dangerous. A new member—typically sponsored by a senior member known as a “carnal” (senior member)—may be required to commit a violent act, such as stabbing or otherwise harming a rival gang member. The act must be carried out under the supervision or approval of existing members to ensure it meets the gang’s standards. Successfully completing such a task demonstrates the recruit’s willingness to uphold the gang’s code of conduct, including the readiness to commit murder if ordered. Failure to comply can result in severe punishment or death, emphasizing the stakes of membership.

Blood-in, blood-out is central to the initiation. The term signifies that membership is permanent: a person cannot leave La Eme voluntarily. The drawing of blood during initiation is both literal and symbolic, marking the recruit as a full member while reinforcing the life-or-death seriousness of the organization’s rules. Following the violent act, tattoos or other symbolic markers—such as the black hand, the number 13, or the eagle and snake emblem—are often applied to indicate formal membership. Additional rituals may include oaths of loyalty, public recognition in front of other members, and instruction on La Eme’s rules, communication methods, and chain of command. The process is designed to reinforce the hierarchy, create strong bonds between members, and embed the recruit fully into the gang’s culture of secrecy, violence, and obedience. La Eme maintains strict requirements regarding age, gender, and ethnicity, reflecting both the gang’s historical roots and its operational priorities. Ethnically, La Eme is exclusively Mexican American. Membership is limited to individuals of Hispanic descent, particularly those with ties to Southern Los Santos neighborhoods and Sureño street gangs. This criterion stems from the gang’s original purpose: to unite Hispanic inmates in prison and protect them from other racial or ethnic groups. Non-Hispanics are generally not allowed to join, although some may work as associates, suppliers, or enforcers without becoming full members. Gender is also strictly regulated: La Eme is a male-only organization. Women are barred from formal membership and are prohibited from participating in gang operations as full members. Female associates may act as couriers, informants, or family liaisons, but they are never granted the rights, privileges, or authority of a male member. This policy aligns with the gang’s historically patriarchal structure and violent, hierarchical culture. Age is more flexible, but there are informal expectations. While there is no legal minimum, members are typically recruited as teenagers or young adults, often while they are active in local Sureño cliques. Younger recruits must demonstrate maturity, toughness, and a capacity to commit acts of violence if required. Older members, particularly those who have served long prison sentences or risen through the ranks, may retain authority and influence well into middle age or beyond, serving as mentors, strategists, or high-ranking carnales. These demographic restrictions ensure that La Eme remains a tight-knit, culturally homogenous organization with shared values, loyalties, and experiences, which reinforces cohesion, secrecy, and discipline across both prison and street operations.Loyalty in [ISP

OILER]La Eme[/ISPOILER] is both a prerequisite for membership and a continuous expectation for life. Before induction, potential recruits are rigorously observed and tested, often over months or even years, to determine whether they possess the commitment, courage, and ruthlessness expected of a carnale. Prospective members are typically asked to carry out tasks that prove their obedience and willingness to engage in criminal acts, including theft, intimidation, or even assault. These tests are designed not only to gauge physical capability but also psychological resilience, ensuring that the individual will follow orders without hesitation or question. Refusal or failure to complete a task usually results in expulsion from consideration, and in some cases, violence or permanent blacklisting. After induction, loyalty remains a daily, enforceable obligation. Members are expected to place La Eme above all else, including family, friends, and personal interests. Violations such as refusing an order, showing disrespect to fellow members, or failing to uphold the gang’s codes can result in severe punishment, ranging from public humiliation to execution. The organization often employs covert monitoring, using trusted lieutenants or associates to report on a member’s conduct. In prison, members are watched for any signs of collaboration with authorities or rival gangs; outside prison, adherence to rules is enforced through intimidation, threats, and sometimes assassination.Loyalty is also tested through participation in major operations, such as collecting taxes from local gangs, enforcing street discipline, or carrying out sanctioned hits. These acts serve as both proof of dedication and a reminder of the consequences of disloyalty. In essence, being “blood in, blood out” is more than a slogan—it is the central measure of a member’s value to La Eme.

OILER]La Eme[/ISPOILER] is both a prerequisite for membership and a continuous expectation for life. Before induction, potential recruits are rigorously observed and tested, often over months or even years, to determine whether they possess the commitment, courage, and ruthlessness expected of a carnale. Prospective members are typically asked to carry out tasks that prove their obedience and willingness to engage in criminal acts, including theft, intimidation, or even assault. These tests are designed not only to gauge physical capability but also psychological resilience, ensuring that the individual will follow orders without hesitation or question. Refusal or failure to complete a task usually results in expulsion from consideration, and in some cases, violence or permanent blacklisting. After induction, loyalty remains a daily, enforceable obligation. Members are expected to place La Eme above all else, including family, friends, and personal interests. Violations such as refusing an order, showing disrespect to fellow members, or failing to uphold the gang’s codes can result in severe punishment, ranging from public humiliation to execution. The organization often employs covert monitoring, using trusted lieutenants or associates to report on a member’s conduct. In prison, members are watched for any signs of collaboration with authorities or rival gangs; outside prison, adherence to rules is enforced through intimidation, threats, and sometimes assassination.Loyalty is also tested through participation in major operations, such as collecting taxes from local gangs, enforcing street discipline, or carrying out sanctioned hits. These acts serve as both proof of dedication and a reminder of the consequences of disloyalty. In essence, being “blood in, blood out” is more than a slogan—it is the central measure of a member’s value to La Eme.La Eme’s influence in Los Santos is extensive, spanning much of the city’s southern and eastern regions, with particular strength in historically Hispanic neighborhoods and blocks. Areas such as East Los Santos, El Corona, Boyle Heights, and parts of the south side have long been under the organization’s sway, often enforced through local Sureño cliques who operate as extensions of La Eme. These cliques, while technically independent street gangs, are obligated to pay “taxes” on drug sales, extortion, and other illicit activity to La Eme, with failure to comply often resulting in violent retribution. Within each neighborhood, control is maintained through a combination of fear, loyalty, and a structured hierarchy. Older, more respected gang leaders act as intermediaries between La Eme leadership—many of whom are incarcerated—and the younger street-level soldiers. They enforce rules, settle disputes, and ensure the collection of tribute from independent drug dealers or smaller crews. Certain corners and blocks are known for specific types of activity, such as narcotics distribution hubs, gambling dens, or smuggling points, all sanctioned and monitored by La Eme affiliates. In addition to traditional gang neighborhoods, La Eme also maintains influence in county jails and detention fa

cilities within Los Santos, where Hispanic inmates are organized into the Mexican car. Here, the gang enforces discipline, resolves internal disputes, and ensures that members who are out on the streets continue to obey its commands. The combination of street-level dominance and incarceration-based authority gives La Eme a near-omnipresent grip on Southern Los Santos, allowing it to operate both overtly and covertly across the city. La Eme marks and enforces its control through a combination of symbolism, intimidation, and structured oversight. On the streets, territorial dominance is made visible through graffiti, murals, and tattoos, with the iconic black hand, the number 13, or the letter “M” serving as constant reminders of the gang’s presence and authority. These symbols communicate to both rivals and residents which blocks, corners, and neighborhoods fall under La Eme’s jurisdiction, and they serve as warnings against encroachment or disrespect. Control is also maintained through direct enforcement. Local Sureño cliques act as the gang’s foot soldiers, tasked with collecting taxes, distributing narcotics, and carrying out orders from higher-ranking members. Disobedience is met with swift and brutal punishment, ranging from physical assaults to targeted murders, depending on the severity of the infraction. The gang relies heavily on fear to ensure compliance, often publicizing retribution as a deterrent. Within prisons and detention centers, authority is reinforced by a strict hierarchy. Senior La Eme members—often serving long sentences—oversee younger inmates and Sureño affiliates, dictating rules for behavior, business operations, and interactions with rival groups. Punishments in these controlled environments are highly ritualized and severe, often requiring that a member who violates the code be stabbed or otherwise harmed by a peer to uphold the gang’s blood-in, blood-out doctrine. Even outside direct conflict, La Eme maintains control by fostering loyalty and dependence. Street-level gang members and small crews are incentivized to cooperate through protection, alliances, and access to criminal networks, creating a system where adherence to La Eme’s authority is both necessary and advantageous. Disputes over territory in Los Santos are resolved through a combination of negotiation, intimidation, and violence, depending on the severity of the conflict and the parties involved. Within La Eme’s network, cliques and street-level crews rarely challenge each other openly without first seeking guidance or approval from higher-ranking members, as unauthorized conflicts could draw lethal consequences. Senior members act as mediators, issuing rulings or setting terms that must be followed to avoid escalating tensions. When negotiations fail or when a rival gang or independent crew refuses to recognize La Eme’s claim, the organization relies on force to enforce its authority. This can range from targeted assaults, vandalism of property, or theft, to full-scale “war” operations that involve coordinated attacks across multiple blocks. Retaliation is swift and often publicized—murals defaced, vehicles set ablaze, or rival members physically assaulted—to send a clear warning that La Eme’s territorial rights are nonnegotiable. The gang also maintains detailed intelligence networks across neighborhoods. Informants and loyal members provide real-time information about rival movements, new crews attempting to encroach, or disagreements within allied cliques. This allows La Eme to act preemptively, preventing small disputes from escalating into larger conflicts and reinforcing the perception that challenges to their territory will be met with decisive and coordinated action. Disputes within La Eme-controlled neighborhoods are treated even more strictly. Any infighting between affiliated cliques is swiftly investigated by senior members, who may assign punishment to individuals responsible or mandate a ritualized resolution to restore order and preserve the gang’s collective authority.

cilities within Los Santos, where Hispanic inmates are organized into the Mexican car. Here, the gang enforces discipline, resolves internal disputes, and ensures that members who are out on the streets continue to obey its commands. The combination of street-level dominance and incarceration-based authority gives La Eme a near-omnipresent grip on Southern Los Santos, allowing it to operate both overtly and covertly across the city. La Eme marks and enforces its control through a combination of symbolism, intimidation, and structured oversight. On the streets, territorial dominance is made visible through graffiti, murals, and tattoos, with the iconic black hand, the number 13, or the letter “M” serving as constant reminders of the gang’s presence and authority. These symbols communicate to both rivals and residents which blocks, corners, and neighborhoods fall under La Eme’s jurisdiction, and they serve as warnings against encroachment or disrespect. Control is also maintained through direct enforcement. Local Sureño cliques act as the gang’s foot soldiers, tasked with collecting taxes, distributing narcotics, and carrying out orders from higher-ranking members. Disobedience is met with swift and brutal punishment, ranging from physical assaults to targeted murders, depending on the severity of the infraction. The gang relies heavily on fear to ensure compliance, often publicizing retribution as a deterrent. Within prisons and detention centers, authority is reinforced by a strict hierarchy. Senior La Eme members—often serving long sentences—oversee younger inmates and Sureño affiliates, dictating rules for behavior, business operations, and interactions with rival groups. Punishments in these controlled environments are highly ritualized and severe, often requiring that a member who violates the code be stabbed or otherwise harmed by a peer to uphold the gang’s blood-in, blood-out doctrine. Even outside direct conflict, La Eme maintains control by fostering loyalty and dependence. Street-level gang members and small crews are incentivized to cooperate through protection, alliances, and access to criminal networks, creating a system where adherence to La Eme’s authority is both necessary and advantageous. Disputes over territory in Los Santos are resolved through a combination of negotiation, intimidation, and violence, depending on the severity of the conflict and the parties involved. Within La Eme’s network, cliques and street-level crews rarely challenge each other openly without first seeking guidance or approval from higher-ranking members, as unauthorized conflicts could draw lethal consequences. Senior members act as mediators, issuing rulings or setting terms that must be followed to avoid escalating tensions. When negotiations fail or when a rival gang or independent crew refuses to recognize La Eme’s claim, the organization relies on force to enforce its authority. This can range from targeted assaults, vandalism of property, or theft, to full-scale “war” operations that involve coordinated attacks across multiple blocks. Retaliation is swift and often publicized—murals defaced, vehicles set ablaze, or rival members physically assaulted—to send a clear warning that La Eme’s territorial rights are nonnegotiable. The gang also maintains detailed intelligence networks across neighborhoods. Informants and loyal members provide real-time information about rival movements, new crews attempting to encroach, or disagreements within allied cliques. This allows La Eme to act preemptively, preventing small disputes from escalating into larger conflicts and reinforcing the perception that challenges to their territory will be met with decisive and coordinated action. Disputes within La Eme-controlled neighborhoods are treated even more strictly. Any infighting between affiliated cliques is swiftly investigated by senior members, who may assign punishment to individuals responsible or mandate a ritualized resolution to restore order and preserve the gang’s collective authority.Street-level gangs in Los Santos function as the operational arms of La Eme, extending the organization’s influence far beyond prison walls. These crews, often called Sureños, are bound to La Eme through a combination of loyalty, fear, and the obligation to pay “taxes” on all criminal activities, including drug sales, extortion, and other illicit enterprises. While each clique may operate semi-autonomously within its neighborhood, all major decisions that impact the broader network—territorial disputes, large-scale robberies, or enforcement of La Eme rules—must be reported to and sanctioned by higher-ranking members. The street gangs act as both enforcers and feeders for the prison hierarchy. They carry out hits, collect tribute, and recruit future members, while also providing intelligence to imprisoned La Eme leaders. This dual role ensures that the organization’s power is cohesive and that orders issued from inside penitentiaries are executed swiftly and effectively on the streets. In essence, the street crews are the visible face of La Eme in the community, implementing the gang’s policies, maintaining control over neighborhoods, and enforcing discipline among both their own members and affiliated crews. Through this structure, La Eme maintains a layered command system. While senior members in prison oversee broad operations and strategy, street-level gang leaders—lieutenants and soldados—manage day-to-day affairs, ensuring loyalty and compliance at the local level. Any deviation from these rules, whether by a small crew or individual member, is swiftly punished, reinforcing the principle that all gangs, regardless of size, are subordinate to the authority of La Eme. La Eme’s financial power comes from a mix of street-level extortion, narcotics trafficking, and organized criminal schemes, both inside and outside the prison system. One of the most lucrative sources is the so-called “tax” or tribute system, whereby street gangs under La Eme’s influence are required to pay a portion of their drug sales, gambling profits, or other illicit earnings to the organization. These payments are collected by trusted intermediaries, often experienced street lieutenants or imprisoned members communicating via coded letters, visits, or improvised signaling systems. Failure to comply can result in brutal enforcement actions, from beatings to targeted killings, ensuring near-total compliance. Drug trafficking remains the backbone of La Eme’s income. The organization exerts control over local narcotics markets in Los Santos neighborhoods by dictating which distributors can operate, the territories they may occupy, and how much they must pay for protection. Inmates who have been released from prison often return to the streets to manage these operations, sometimes forming small crews to oversee sales and distribution while funneling the majority of profits back to the gang’s leadership. Beyond traditional street drugs, La Eme has also adapted to newer markets, including fentanyl, methamphetamine, and other synthetic substances, maintaining influence over supply chains and ensuring dominance in the competitive Los Santos drug scene. Extortion extends beyond street-level gangs and dealers to include local business owners. Establishments in neighborhoods controlled by La Eme are expected to pay for protection, often under threat of property damage, arson, or violence against employees and family members. This enforcement of “protection fees” generates substantial revenue while simultaneously reinforcing La Eme’s reputation as an organization that cannot be challenged without severe consequences. Other financial schemes include illegal gambling operations, loan-sharking, and money laundering. By embedding these activities within community net

works and leveraging loyal street-level operatives, La Eme maintains a diversified income portfolio that allows it to remain financially resilient, fund prison operations, and sustain the loyalty of its members through gifts, bail payments, or other incentives.

works and leveraging loyal street-level operatives, La Eme maintains a diversified income portfolio that allows it to remain financially resilient, fund prison operations, and sustain the loyalty of its members through gifts, bail payments, or other incentives.La Eme enforces its tribute system with a highly organized and often ruthless approach that spans both the streets of Los Santos and the prison system. Collection of “taxes” is usually carried out by trusted lieutenants or veteran members who act as intermediaries between the gang’s leadership—often incarcerated—and street-level crews. These intermediaries maintain communication through coded letters, body language during visits, contraband signals, or even improvised methods such as tapping on pipes and walls, which allows them to issue orders and confirm payments without exposing the gang to law enforcement. On the streets, tribute is collected in several ways. Local Sureño-affiliated gangs operating in neighborhoods under La Eme’s influence are required to set aside a portion of their drug proceeds, gambling revenue, or other illicit earnings for their higher-ups. Payments are typically demanded on a weekly or monthly basis and are tracked carefully; missing a payment is interpreted as defiance. Enforcement is immediate and brutal—failure to pay can lead to violent beatings, targeted assaults, or even murder. These acts serve both to punish defiance and to intimidate other crews into compliance, reinforcing La Eme’s authority across multiple neighborhoods. In prison, collection and enforcement are similarly structured but adapted to the environment. Members known as “soldados” are assigned to monitor fellow inmates who control external revenue streams or influence street-level operations. Any delays or failures in tribute payments are reported up the chain of command, often resulting in beatings or orders for contract killings once the involved parties are released or transferred. The fear of retaliation ensures that even incarcerated members respect the tribute system. Additionally, La Eme maintains oversight through a network of informants, couriers, and peripheral associates. This network allows leaders to know which crews are underperforming or attempting to evade tribute without exposing themselves directly. Some high-ranking members also exercise authority remotely by giving explicit orders to enforce payments, instructing loyal enforcers to carry out punishment or intimidation as necessary. This combination of fear, strict hierarchy, and meticulous oversight ensures that the tribute system functions as both a reliable income source and a tool for maintaining control across Los Santos. La Eme runs a wide array of secondary operations that complement their main income streams of drug trafficking and extortion. Gambling is one of the most common, ranging from underground card games and dice games in bars, back rooms, and private homes to more organized sports betting rings. Street-level crews under La Eme’s oversight often manage these operations, with a portion of profits funneled up to the leadership as part of the tribute system. The organization enforces strict rules in these operations, ensuring that disputes over winnings or cheating are punished swiftly and harshly to maintain both order and intimidation. Theft, robbery, and burglary also play a significant role in La Eme’s criminal enterprise. These acts are usually strategic rather than opportunistic; high-value targets are chosen carefully to maximize profit while minimizing exposure to law enforcement. Stolen goods—ranging from electronics and vehicles to cash and jewelry—can be fenced through La Eme-connected networks or sold within controlled neighborhoods. Members are often required to turn over a portion of their haul to higher-ranking gang members, reinforcing the hierarchical structure and loyalty expectations. Other secondary operations include prostitution rings, loan-sharking, and small-scale arms trafficking. Prostitution is typically controlled indirectly, with certain street crews overseeing the recruitment and protection of sex workers, while profits are shared up the chain. Loan-sharking provides both revenue and leverage over local crews, as debts are often enforced violently to ensure compliance. Weapons sales, while smaller in scale compared to drugs, are crucial for arming members, enforcing rules, and maintaining the gang’s reputation for brutality. Finally, La Eme often exploits legal or quasi-legal enterprises for money laundering and operational cover. Small businesses such as auto shops, car washes, liquor stores, or construction fronts can be used to clean illicit funds, stage meetings, or hide the movement of goods and personnel. These operations demonstrate La Eme’s adaptability—allowing the organization to maintain financial strength, strategic control, and influence over the neighborhoods and streets of Los Santos even under constant law enforcement scrutiny. Street and prison operations coordinate financially through a layered, trust‑based network that moves value without relying on any single person or obvious paper trail. At the top level, incarcerated leaders set quotas and expectations for tribute: broad percentages, priority payments (taxes on high‑value narcotics, protection fees, cut from gambling racks), and occasional special levies (bail money, funeral collections, payments for sanctioned hits). Those directives are passed down to trusted camaradas and soldado lieutenants who operate on the streets; those lieutenants are responsible for translating orders into collections and for making sure the money actually arrives where it’s supposed to. That separation—orders coming from the inside, collections happening outside—creates redundancy and deniability while keeping operational control with the prison leadership.